Achieving the right balance between what Jung called the ego and self is central to his theory of personality development

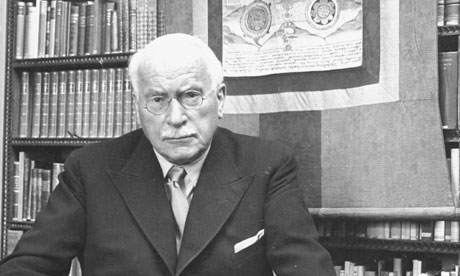

As a child, Carl Jung believed he had two personalities, which he later identified as the ego and the self. Photograph: Dmitri Kessel/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

If you have ever thought of yourself as an introvert or extrovert; if you've ever deployed the notions of the archetypal or collective unconscious; if you've ever loved or loathed the new age; if you have ever done a Myers-Briggs personality or spirituality test; if you've ever been in counselling and sat opposite your therapist rather than lain on the couch – in all these cases, there's one man you can thank: Carl Gustav Jung.

The Swiss psychologist was born in 1875 and died on 6 June 1961, 50 years ago next week. His father was a village pastor. His grandfather – also Carl Gustav – was a physician and rector of Basel University. He was also rumoured to be an illegitimate son of Goethe, a myth Carl Gustav junior enjoyed, not least when he grew disappointed with his father's doubt-ridden Protestantism. Jung felt "a most vehement pity" for his father, and "saw how hopelessly he was entrapped by the church and its theological teaching", as he wrote in his autobiographical book,Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

Jung's mother was a more powerful figure, though she seems to have had a split personality. On the surface she came across as a conventional pastor's wife, but she was "unreliable", as Jung put it. She suffered from breakdowns. And, differently again, she would occasionally speak with a voice of authority that seemed not to be her own. When Jung's father died, she spoke to her son like an oracle, declaring: "He died in time for you."

In short, his childhood was disturbed, and he developed a schizoid personality, becoming withdrawn and aloof. In fact, he came to think that he had two personalities, which he named No 1 and No 2.

No 1 was the child of his parents and times. No 2, though, was a timeless individual, "having no definable character at all – born, living, dead, everything in one, a total vision of life". (At school, his peers seem to have picked this up, as his nickname was "Father Abraham".)

Jung was perhaps not so unusual, as many children indulge similar internal fantasies. Where Jung differed was in taking his inner life seriously. "I have always tried to make room for anything that wanted to come from within," he noted. Later he renamed and generalised No 1 and No 2, calling them the ego and the self. Achieving the right balance between the two aspects of the psyche is central to his theory of personality development, called individuation.

Jung finally came into his own at university. He proved himself a brilliant student, developing "a tremendous appetite on all fronts", graduating in medicine and natural science in double-quick time. His first public paper was entitled On the Limits of the Exact Sciences, in which he questioned an inflexible philosophy of materialism. His doctorate was On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena, and laid the foundations for two key ideas in his thought. First, that the unconscious contains part-personalities, called complexes. One way in which they can reveal themselves is in occult phenomena. Second, most of the work of personality development is done at the unconscious level.

He first made a name for himself in the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital in Zürich, working with Eugen Bleuler, the doctor who coined the word "schizophrenia". Jung developed the word association test of Francis Galton, the cousin of Charles Darwin.

A patient was read a list of words and asked to respond to each one with the first word that comes into their mind. The response, and the time taken to produce it, is recorded.

Previous research had already demonstrated that prolonged response times indicate that the stimulus word unconsciously troubles the patient. Sometimes, it is possible to identify a group of such words. Jung's contribution was to link these groups with the unconscious part-personalities and show how the test provides a window into the distressed world of the mentally ill. People are not simply mad, he concluded. Rather, there is a method in their madness. In one case, Jung showed that a patient who for 50 years had been fixated on the apparently meaningless task of making illusory shoes, had been abandoned by a lover who was a cobbler.

Jung was becoming quite well known, with his fame in Zürich prompting the first of several questions that subsequently came to dog his reputation. It concerns his alleged womanising.

At university, he discovered that he could sway an audience with the force of his character and ingenuity of his ideas. In Zürich, he gave public talks. "Clusters of women formed a phalanx around him before and after each of his lectures," writes Deidre Bair in her seminalbiography. Then, a woman called Sabina Spielrein became his patient and, it was rumoured, his lover – perhaps just one of many. Later, he certainly formed a ménage à trois with Toni Wolff, to which his wife Emma only slowly became reconciled. Sleeping with patients is now the unforgivable sin among psychotherapists. Had Jung committed it?

After examining the evidence over several chapters, Bair concludes that it is impossible to discover the truth of what happened, though the rumours and speculation appear wildly exaggerated. After all, this was an age in which husbands and wives would greet each other with a chaste shake of the hand, even in private.

Jung had an electric personality. It is hardly surprising that such charisma was interpreted as erotically unsettlingly.

Further, the phenomenon of patients developing powerful feelings for their therapists – part of what is called transference – was then new. Freud's earliest collaborator, Josef Breuer, dropped the "talking cure" when one of his patients didn't just fall in love with him but developed a phantom pregnancy, naming him as the father. Freud first thought that transference was unhelpful and should be circumvented. Then, he came to believe that it was the cornerstone of psychodynamic therapy because it brings back to life otherwise buried feelings and affections.

But that brings us to Jung's encounter with the founder of psychoanalysis. We will explore that transformative experience next week.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario